Sometime in early 2010, Railway Ministry officials in New Delhi began noting a sudden increase in demand for empty wagons from Bihar. Adding to their curiosity was it being courtesy of a single commodity — maize (corn) — transported out of the state. Till 2006-07, hardly 40-50 rail rakes, each carrying 2,600 tonnes of maize, were getting loaded annually from three sidings at Khagaria, Mansi, and Naugachia. But over the next 6-7 years, these had risen to 500-550 rakes while being moved from 16-odd railway sidings across central and eastern Bihar.

“The Railway Board people were surprised to see such a jump in dry bulk cargo volumes ex-Bihar, that too from just maize. They were, then, naturally keen to know what was happening,” recalls BK Anand, Director & Business Head (Grains and Oilseeds) at Cargill India Pvt. Ltd. Behind this unusual spurt in freight traffic was a little-reported story of a corn revolution in an unlikely state.

Bihar, of course, always had the potential to be an agricultural powerhouse, given its naturally fertile soil and the abundant water resources from the Ganga and its tributaries crisscrossing the state. Moreover, the scope for growing high-yielding maize during the rabi season – planting in October-December and harvesting in April-June – was recognized even back in the 1960s. The long cropping duration, mild temperatures with clear skies, absence of flooding, and low pest and disease infestation during this period allowed farmers to obtain yields at least twice that from the regular post-monsoon kharif season.

That potential was, however, realized only in the last decade, with Bihar’s rabi maize output doubling from 10.64 to 21.26 lakh tonnes (lt) between 2005-06 and 2013-14. Actual production may even be more, at 30 lt-plus, since the official data reckons average rabi yields to be below 20 quintals per acre. “Going by the near-universal penetration of hybrids now, the average yield might be closer to 30 quintals,” admits a senior state agriculture department official.

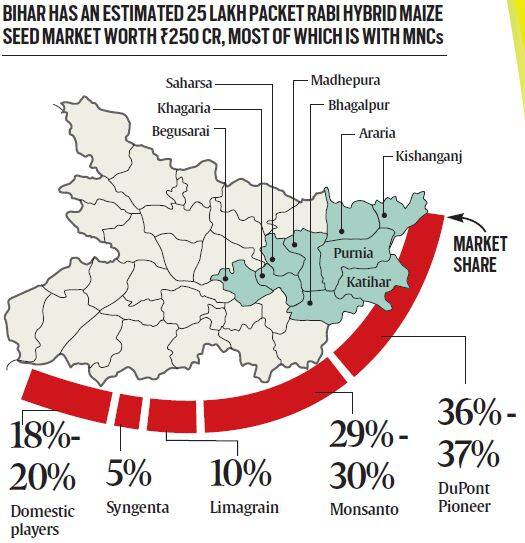

This doubling, if not trebling, of output has been largely a private sector multinational-led revolution similar to that in Bt cotton. Bihar today has an estimated 25-lakh packet rabi hybrid maize seed market, worth Rs 250 crore at an average of Rs 1,000 per packet of 4 kg. A major share of this is with MNCs: DuPont Pioneer (36-37 percent), Monsanto (29-30 percent), Limagrain (10 percent), and Syngenta (5 percent). The balance is accounted for by domestic players like Nuziveedu and Kaveri Seeds.

While technology — the planting of high-yielding single-cross hybrids — has played a major role in raising Bihar’s maize production, the real breakthrough, though, came with surging export demand.

From around 2006-07, MNC traders led by Cargill started sourcing maize from Bihar for supplying to Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam traditionally imported maize from South America. Bihar’s advantage was that its corn arrived in the markets in early May and could be shipped out from Visakhapatnam or Kakinada ports by end-May, whereas the South American crop wasn’t ready for despatch before mid-June.

Add to this the lower voyage time to South-East Asian ports (20 days compared to 45 days from Brazil or Argentina) and the flexibility to ship out in smaller Handy/ Handymax vessels of 30,000-40,000 tonnes capacity (as against the 65,000 tonnes-plus Panamax cargoes from Latin America), it was clear why everyone from Cargill to Louis Dreyfus, Glencore, Noble Grain and Bunge were descending on Bihar.

By 2012-13, Bihar’s annual maize exports had crossed 10 lt – 6.5 lt to South-East Asia and 3.5 lt to Bangladesh and Nepal. That was also the year when world corn prices peaked, with landed costs at Indonesia’s Cigading or Malaysia’s Klang ports averaging $ 310-315 a tonne. Global traders offered rabi maize from Bihar for $10-15 cheaper, leveraging both its location advantage and the nearly two-month-long time gap for South American shipment arrivals. The export boom also benefited Bihar’s farmers, who saw their price realizations soar from Rs 400 to Rs 1,200 per quintal between 2005 and 2012. The stretch from Purnia, Katihar, and Bhagalpur to Madhepura, Saharsa, Khagaria, and Samastipur – north of the Ganga and on either side of the Kosi – emerged as a corn belt where many farmers, big and small, harvested 50 quintals or more per acre. That was comparable to the 180-200 bushel yields in the US Midwest heartland of Illinois, Iowa, and Indiana (one bushel equals 25.4 kg). In the flood-prone areas of Khagaria, Saharsa, Samastipur, and Katihar, rabi maize became the major and, in some cases, the only crop.

Hoardings of seed companies are a common sight in Bihar’s corn belt. (Express Photo by: Prashant Ravi)

“It is impossible for us to grow any kharif crop, as our fields are fully inundated from July to September. Sowing can happen only after mid-October when the flood waters recede. We put all our energy now in rabi maize, which gives far higher returns than wheat or boro (winter) paddy”, says Pappu Mandal, a farmer from Bharri village in Katihar’s Kadwa block, a low-lying area about 5 km from the Mahananda river that overflows during the monsoon months.

Much of Mandal’s 30 bigha holding has been planted to P-3522, a maize hybrid of DuPont-Pioneer yielding an average of 20 quintals a bigha or 50 quintals per acre over a six-month cropping period. “Makka (maize) is a 100 percent commercial crop. Till 5-7 years back, you could lease agricultural land here at Rs 5,000-6,000 per acre per year. That has now gone up to Rs 17,000-18,000 only due to makka”, notes Mohammad Asrar, a 10-acre grower from Kajha in Krityanand Nagar block of Purnia who is also a village-level aggregator-cum-trader (kachha arhatiya) of the produce of other farmers.

Bihar’s corn revolution has, however, been dealt a severe blow with the crash in global commodity prices in the last year. With landed rates in Southeast Asia sliding to $ 190-200 a tonne, maize exports have turned unviable. The only exports happening from Bihar today are to Bangladesh and Nepal. Farmers’ realizations, as a result, have dropped to Rs 950-1,000 per quintal in the current marketing season. “There is a problem when export demand dries up and we don’t have processing units within the state to absorb the surplus maize”, acknowledges Vijay Prakash, Bihar’s Agriculture Production Commissioner.

Bihar does have poultry feed mills, mainly in the Muzaffarpur-Hajipur region, but these are typically of 150-200 tonnes per day (tpd) capacity. This compares to the 1,000-1,200 tpd capacity feed mills in the South or the 1,000-tpd modified corn starch facilities that multinationals like Cargill and Roquette have put up in Karnataka. That, in turn, has to do with Bihar’s old problem: the lack of reliable infrastructure (especially power) and proactive administration, which are dampeners to attracting investments even in agro-processing. It’s a challenge the next government at Patna, irrespective of who leads it, will need to address.

India’s Freest Grain Mandi

It is India’s largest mandi for maize. With estimated annual arrivals of 5-6 lakh tonnes — 7,500-10,000 tonnes daily during the peak season from mid-April to mid-July — it is, indeed, as big as the more famous grain mandis of Khanna or Rajpura in Punjab.

But Gulab Bagh near Purnia is also India’s ‘freest’ grain market. This is because Bihar does not impose any value-added tax on maize, and there is also no mandi fee, thanks to the Nitish Kumar government repealing the state’s Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee (APMC) Act in 2006.

As a result, there are no administrative impediments to the marketing of produce at this mandi or the farmer/village aggregator, even delivering maize directly at the railway rake points of Purnia, Ranipatra, and Jalalgarh. About 100 rakes, each of 2,600 tonnes, are moved every year from these three sidings that are within 25 km of Gulab Bagh.

But the flip side of such a “free” market is the absence of any regulation or proper infrastructure. Unlike the marketing yards in Punjab or Madhya Pradesh, there are no pucca roads, street lights, drainage, running water, rain shelter, or restroom facilities in the 56-acre Gulab Bagh mandi complex.

“With the repealing of the APMC Act, there is no marketing board responsible for developing and maintaining infrastructure here. It makes sense to levy a small cess on grain purchases, whose proceeds can be earmarked towards ensuring basic marketing facilities”, observes Surya Mohan Jaiswal, a trader-cum-commission agent (pucca arhatiya) here.

Even worse is the lack of trading regulations, which invariably work against farmers. Gulab Bagh has 150-odd pucca arhatiyas — mostly Marwaris and local Banias, with a sprinkling of Yadavs — of whom around 10 do business of 25,000-50,000 tonnes each per season, mainly for multinational traders and large feed mills.

“The whole system is non-transparent. Although they say it is an open bazaar, the big traders decide the price and even grain quality by just looking or feeling without any moisture meters”, alleges Vinod Choudhary, a 60-acre farmer from Damaili in Purnia’s Dhamdaha block.

Gulab Bagh traders have also evolved their own quality nomenclature for the grain brought to the mandi.

The best quality maize, with optimal moisture percentage and low broken/damaged grain content, is called “Shalimar Calcutta Pass,” after a Kolkata-based poultry feed company. Next in the hierarchy is “Super Bangladesh” or SBD, followed by plain Bangladesh (“BD”), and finally, RBD (“Reject Bangladesh”), which fetches the lowest price.

Manning the Fields

He is the progressive Achcha Kisan every multinational seed company would love. This 60-acre Bhumihar farmer grows Monsanto’s Dekalb-9120 and DuPont Pioneer’s P-3522 maize hybrids on 25 acres while maintaining a 20-acre mango orchard and planting wheat and mustard in his remaining land. At 60 quintals per acre, his maize yields are the highest in Bihar and probably India.

But Choudhary is also a maize trader, selling about 60,000 quintals annually, including his own 1,500 quintals, besides dealing in fertilizers and hybrid corn seeds. He has built a warehouse that can store 1,500 quintals: “Instead of going to the mandi, I have tied up Suguna Poultry, Amrit Feeds, and a few other processors in Siliguri. They lift directly from my warehouse and give a better rate than the dalals (brokers) in Gulab Bagh”.

Choudhary’s biggest concern is labor costs: “Five years back, if you wanted five people and offered Rs 50 daily wage along with food, eight would turn up. Now, even with Rs 200 plus food, only two will come”.

Unlike Choudhary, this father of four sons (one of who works as a farm labourer in Punjab) and three daughters owns no land.

That hasn’t stopped Mohammad Mahir, though, from growing Pinnacle, a high-management irrigated maize hybrid from Monsanto, on 22 bighas under a ‘batai’ sharecropping arrangement where one-third of his produce goes as lease rent to the landowner.

At 20.5 quintals per bigha — 2.5 bighas make an acre — his yields are as good as the 200-bushel levels of farmers in Illinois and Iowa. Mahir estimates his total cultivation cost at Rs 9,000-10,000 per bigha, including Rs 1,150 for seed, Rs 2,800 for fertilizer, Rs 1,500 for pesticides, Rs 1,400 for irrigation, and Rs 2,500 for threshing and transport. “Even at a price of Rs 900 per quintal, I get a reasonable return”, he says.

Mahir’s main cost saving comes from the “free” labour contributed by family members. “This crop needs good care, but it is only makka that helped me get two of my daughters married,” he reveals.

Given half a chance, he would grow maize even in the aangan (courtyard) of his home.

Shankar Singh hasn’t revised that opinion even after cyclonic winds damaged almost half of his crop this year. Like most farmers in this Rajput-dominated village, his entire 12-acre holding was planted with maize.

Makka cultivation, according to Singh, is like a fixed deposit that doubles in six months. “Farmers here are much better off than what they were 6-7 years back. Earlier, we used to grow bananas, and some of us also tried out sunflower. But with Makka, I have been getting Rs 2.5-3 lakh annual profits, which has been solely due to good-quality hybrids giving over 50 quintals per acre”, he adds.

Chandwa, which has 100-odd farming families, is part of Falka, the block that was worst affected by the thunderstorm and squall lashing Bihar’s Seemanchal belt on the night of April 21. “Seeing our crop lodge made me understand what drives farmers to commit suicide. But I believe the cyclone was an aberration, and we will come back strongly in the next maize season”, asserts Singh.